In 1960, one of Australia’s leading architects and recipient of the prestigious Australian Institute of Architects Gold Medal, Robin Boyd, offered a scathing and unbridled critique on Australia’s built environment in his book The Australian Ugliness. Boyd railed against gratuitous “featurism” of objects and buildings saturated in pointless ornamental embellishments, the embarrassing “cultural cringe” of decorative kitsch such as velvet lounges and boomerang coffee-tables, and the “visual squalor” of discombobulated cities, towns and suburbs. Initially criticised for being unpatriotic, Boyd was later lauded as a visionary and his dissertation on Australian design, culture and architecture is now widely regarded as one of the most important pieces of literature on the topic. The Australian Ugliness perhaps references a confused and uncertain period in both our architectural and national identity where we were shaking off the parental influence of England with its conservative ideals, and also looking to our ‘big brothers’ in America and Europe to emulate. So are we still in our awkward self-aware adolescent phase or has the ugly duckling emerged into a swan that makes a significant contribution to the national and indeed international architectural landscape? With only a 200-odd year history it is easy to traverse our architectural timeline. Our formative years were defined by British colonialism, which merely sought to establish Australian architecture as an extension of popular Georgian styles from convict prisons to military barracks and government buildings, designed by our nation’s first Architect, the convict Francis Greenway. During the 19th century, Australian architects continued to replicate English architectural trends such as the Neo-Gothic and Victorian movements for major public buildings, whilst new Australian settlers hewed materials from the rugged environment to create the earliest cottages, homes, and then homesteads (which saw the emergence of the Queenslander style). By the turn of the 20th Century, and coinciding with the Federation of Australia, Australia began to asset its own style, Federation, which was a derivative of the Edwardian architecture that embraced Australian themes such as flora and fauna in its decorative motifs. After World War I, North American and International influences started to appear with the wave of European immigration and advanced communications. This era represented a post-war boom which saw the emergency of multiple styles of public buildings (such as Art Deco, and skyscraper Gothic) and housing (such as Tudor and the Californian bungalow). In the years following World War II, the Austere style reflected the lack of availability of building materials and labour. With the population boom and lingering economic challenges driving the need for cheaper housing, the design of housing was mostly undertaken by builders and did not contribute any aesthetic or environmental virtue. Australian architecture in the 50s and 60s did see the notable local emergence of the global modernist styles that sought to simplify and elevate form and function over historical affectations and derivations. Boyd and Harry Seidler (whose residential homes embraced the principles of the Bauhaus) were key local visionaries in this movement. The “Ugly Australia” that Boyd was denouncing in this period, however, was found in the expanding suburban outskirts: New shapeless suburbs sprawl heartily on the surrounding country. They grow without grace, without charm, far beyond the recall of the metropolitan transport system, beyond the last call of the milkman, beyond the gas, the sewerage, the shops, the theatres, the hotels… (Robin Boyd, The Age, 1948) This aesthetic was largely motivated by the “Great Australian Dream,” and saw families assert their collective prerogative to own their own land, house and backyard. This created a low-density sprawl which further swelled to the outskirts of our major cities. It also gave rise to the ubiquitous ‘brick veneer house’ whose standardised construction and cheap building materials allowed the housing dream to be a reality for the everyday Australian, but at the cost of proximity to the CBD centres and a cohesive and creative design identity. Moving forward into the late twentieth-century (1960 – 2000) public and private architectural diversity in Australia exploded, with 14 defined different architectural styles defined. These included: International (Australia Square); Organic (New Parliament House, Canberra); Brutalist (National Gallery of Victoria); Structuralist (Sydney Opera House and Canberra’s Shine Dome); Late Modern (Melbourne’s Rialto and Sydney’s Governor Phillip Tower); and Post-Modern (Chiefly Tower). No one architect or movement rose to prominence but rather we seemed to be experimenting with a variety of styles that have created the look and feel of our major CBD’s today. Likewise, today’s outer suburbs are a legacy of this eclectic and erratic sampling of the mid to late twentieth-century period. It could be argued that the “Ugly Australia” of Boyd’s denouncing is equally prevalent today where sound twentieth-century architectural movements and principles (Deconstructivist, Post-modern, Structuralist, Sustainable, and Modern) are bastardised by the mass housing market in a cheap and clumsy copy of the original without appreciation for design concepts or environmental and sustainable contexts. Poorer metropolitan areas are prolific with extravagant, kitschy mansion-style homes that fail to match with the remaining houses in the street and contribute nothing to the cultural expression or dynamic of the suburbs. Despite Australian architects such as Kerry Hill, Nonda Katsalidis and Glenn Murcutt, together practices such as Bates Smart, Woods Bagot and Hassell punching above their weight with internationally lauded buildings (many of which straddle the globe), the principles behind those successful buildings do not generally translate into the built mass residential environment. It still seems the greatest issue facing modern Australian architecture is not the shortage of innovative ideas and progressive architects, but how to translate this design aesthetic to the modern Australian family in the ever-expanding and increasingly unsightly outer suburbia in an affordable (and tasteful) manner. Perhaps the answer lies back with Boyd. His greatest legacy may not have been the seminal book that woke us up to our ludicrous and decidedly ugly suburbs, but the fact that he then spurred passionate debate and actively contributed to the solution. As Director of the Victorian chapter of the Australian Institute of Architects, Boyd formed the Small Homes Service with Melbourne broadsheet The Age, which published a weekly column on the emerging ideas of Modernism. By firstly showing the drawing and template of the house (of which the full architectural drawings could be purchased by an owner-builder for £5), and then explaining the rationale for it, he began to educate, motivate and enable Australians to take part in a very sophisticated form of DIY. The impact of the Service was unprecedented with Boyd’s own reports stating that through 1948-1949, 20 per cent of houses built in Melbourne were using Small Homes Service plans, compared with modern estimates that currently only 5 per cent of housing in Australia has architectural involvement. Boyd’s writing expressed strong views about the links between popular culture and architecture and that design should penetrate all levels of culture, not just the stand-alone great building. He proposed that education in design, landscaping and architecture can be a means to resolve the ugliness he observed. Now, as then, education and public participation is the key to beautifying our country’s suburban sprawl, or at least creating a public conversation on the importance of architecture to our lives. What is needed is certainly ongoing support for Australian architects to do great things in our city centres and around the world, however, we also need a way to make the architectural movements relevant to the everyday Australian. Architectural design shouldn’t be elitist and inaccessible, but something that is practical and translatable for everyday Australians. Then, with innovative directions, national engagement, and viable implementation filtering down to great emerging suburban design, we can truly shrug off the ‘ugly’ Australian moniker. Header Icon

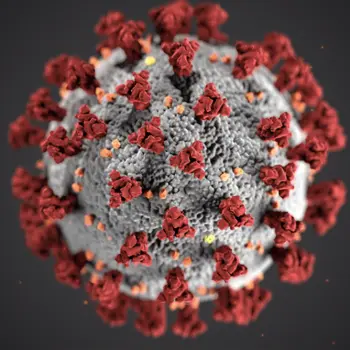

December 2019 Covid Update

Updated 7/12/20 The Office Space’s COVID-19 Safety Plan outlines our commitment to providing a carefully managed workspace that upholds the guidelines and the best practice advice of NSW Health, the Federal Government…

Read More